April 2007 Newsletter: Experimental thyroid surgery

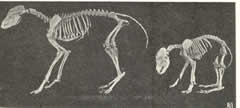

Our understanding of thyroid physiology is largely based upon the outcomes of experimental thyroid surgery in animals. Schiff (1859) first described the striking results of ablation of the thyroid in experimental animals but it was not until 1884 that the matter was put on a firm basis by the same observer. He then also showed that by means of homotransplants of the thyroid, the consequences of thyroidectomy could be avoided, and foreshadowed the possibility of emulsions of the gland having a similar effect. Many of the earlier experiments were invalidated by the coincident removal of the parathyroids so that a complicated picture of thyroid and parathyroid deprivation resulted. Horsley (1886) by his expeiments on monkeys, followed up and confirmed Schiff’s work, although for a time Munk (1887) attributed Horsley’s results to injuries to the sympathetic nerves. Sutherland Simpson (1913) and Basinger (1916) working with sheep and rabbits respectively, obtained effects similar to those of Schiff and Horsley, although on the whole the severity of the symptoms in the herbivora was less than in the carnivora with which Schiff worked. The symptom complex which these animals showed was exactly similar to that of sporadic cretinism, know at the time to be associated with thyroid atrophy. In rabbits for example, the first indications are seen after two weeks. The hair becomes drier and can easily be pulled out. Retardation of growth is noted as early as the third week, reaching a maximum between the eighth and twelfth. The animals remain immobile for hours unless disturbed, and if stimulated, move awkwardly and slowly. The bones are short, the muscles flabby and too weak to support the body weight, while the abdomen is distended, as in the pot belly of the human cretin, and a characteristic posture is assumed.

From “Diseases of the Thyroid Gland”. Cecil A Joll, 1932. William Heinemann, London.